The 1970s saw an awakening of homeless activism movement in Washington, DC. Gentrification and a changing housing market left neighborhoods filled with vacant homes, forcing their former occupants to live on the streets. In response, a group of students from George Washington University joined Father Guinan in creating the Community for Creative Non-Violence in 1970.[1] After joining CCNV in 1973, Snyder quickly became involved in the group’s activities. He, along with others in the group, were increasingly concerned about the number of people being displaced from their homes in Columbia Heights, a neighborhood in Northwest D.C. To address this issue, CCNV and Snyder spearheaded an initiative to create a shelter in an abandoned home on Fairmont Street in Northwest D.C.

The once vibrant and predominantly African American neighborhoods in Columbia Heights were by the 1970s increasingly becoming rows of vacant and decaying buildings. This visible dilapidation was a byproduct of what became known as the 14th Street urban renewal area. The plans to revitalize the neighborhood heavily influenced developers and landowners behavior who began to speculate in property hoping that its value would increase in the future. By the mid-1970s, they evicted an estimated five families a week as they warehoused homes for future redevelopment. In 1976, Mitch Snyder observed, “The neighborhood is about to go the route of Adams-Morgan, Capitol Hill and Georgetown. The absentee landlords will soon begin to rehabilitate. Sale and rental prices will skyrocket. The people will be driven out of what little shelter they now have.”[2]

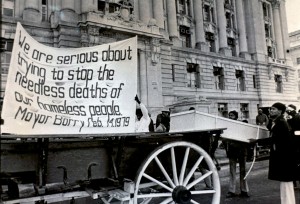

In 1975 alone, approximately 10,000 people were put on the streets as a result of evictions in Washington, D.C. In the face of freezing winter temperatures, these homeless found some protection camping on steam grates and huddling around fires in vacant lots.[3] Nonetheless, the city began seeing deaths from exposure as nine homeless individuals in 1976 and at least eight in 1977 died on the streets.[4] These deaths seared into the consciousness of Mitch Snyder and other CCNV activists and prompted a series of protests and direct actions.

Feeling the D.C. government did little to address the crisis, in 1976 Snyder and CCNV took over and rehabilitated a vacant house at 1361 Fairmont St. NW in the heart of the Columbia Heights neighborhood.[5] This house sat empty for more than seven years before CCNV activists occupied it and demanded the D.C. government use it as an emergency homeless shelter.[6] The city eventually granted the group permission to renovate the building, but in 1978 officials took back control of the Fairmont house and tore it down reportedly for safety reasons.[7]

The struggle over Fairmount House set the stage for the subsequent fight over the building that currently houses CCNV. Following a series of lengthy hunger strikes led by Mitch Snyder, the Reagan administration reluctantly agreed in 1986 to rehabilitate and turn over the Federal City College building to Washington, D.C. Threatening to undercut the deal, the city argued that they only wanted the building if they had the right to sell it. In a congressional hearing, representatives from the city unconvincingly argued that centrally located mega-shelters were inferior to smaller shelters dispersed in the neighborhoods.[8] CCNV activists, on the other hand, had grown convinced in the value of a centrally located shelter whose residents had good access to social services.

While the struggle shifted from a northwest neighborhood to downtown, and the activism focused increasingly on the federal rather than the local government, it was not a coincidence that this early fight over Fairmont House happened to take place in Columbia Heights. The radical transformation and subsequent gentrification of that neighborhood played a significant role in dispossessing people of their homes and making housing less and less affordable in the city.

[1] Community for Creative Non-Violence. “History of the CCNV.” (2009) http://www.theccnv.org/history.htm.

[2] Colman McCarthy. “Empty Houses and the Homeless Poor.” The Washington Post (1976, Dec 8) A27.

[3] Juan Williams. “Street People Sleep on Steam-Heated Beds: Steam Vents Are Beds For the Street People.” The Washington Post (1977, Feb 3) C1.

[4] Paul W. Valentine. “Officials Back Visitor Center Use as Shelter: Visitor Center Use as Shelter Is Planned.” The Washington Post (1978, Nov 30) B1.

[5] Colman, A27.

[6] Juan Williams. “D.C. Rejects Plan To Shelter Evictees.” The Washington Post (1976, Aug 5); “3 Are Arrested In New Effort to Occupy House.” The Washington Post (1976, Aug 17).

[7] Elwell, 59.

[8] U.S. House, Committee on Government Operations, Transfer Jurisdiction of Property for Homeless Shelter (H. Rpt. 99-616). Washington Government Printing Office, 1986.