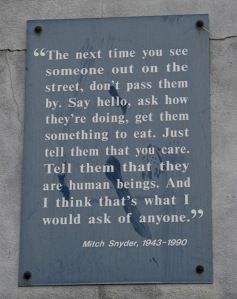

A key turning point in the homeless advocacy movement in Washington, D.C., and perhaps nation-wide, occurred after public icon and activist, Mitch Snyder, committed suicide in July of 1990. Arguably the most public advocate for the homeless in D.C. and former director of the Community for Creative Non-Violence (CCNV), Snyder was known nation-wide for his radical, direct action tactics in support of shelter for the homeless. Most famously he led an occupation of the Federal City Shelter followed by a 51-day hunger strike to secure federal funds to renovate the building.

Mark Anderson, an activist who had been inspired by Snyder’s work, reflects on the significance of Snyder’s death.[1]

Following Snyder’s death, tensions within CCNV flared. The 1990s, flanked with controversy, marked a turbulent and transformative time within the organization’s history. Furthermore, these tensions were a part of a larger shift within the homeless and unhoused “advocacy” movement from engaging in protest and radical direct action to promoting service delivery and organizational stability.

The first years after Snyder’s death were filled with many setbacks for the homeless and housing advocates in the D.C. area. First, Initiative 17 – the D.C. law that guaranteed overnight shelter to any homeless person – expired and was not renewed by District voters in 1991. Failure to abide by the right to shelter had cost the city over $3.6 million in fines.[2] Furthermore, city budget dedicated to services for the homeless sharply decreased in the early ‘90s, with cuts as high as $4 million in 1994.[3] These setbacks signaled the emergence of a backlash against the homeless advocacy movement.

The death of Snyder left a public leadership vacuum at this pivotal moment in time. Christine Spolar, journalist for The Washington Post wrote: “What is apparent… is that no other advocate had his [Snyder] ability to make homelessness a headline, to infuriate the establishment into action or to command compassion for the jobless, the mentally ill and the addicted who end up in shelters… Who or what will take his place?”[4]

Specifically at CCNV, scandal hit the shelter after a “60 Minutes” expose aired on national television in December of 1993 and showed some CCNV staff and residents “allegedly selling donated food and clothing and illegal drugs.”[5] The episode escalated tensions within the CCNV community. In early 1994 the CCNV board voted to remove Carol Fennelly as shelter director and Cliff Newman as CCNV vice president. Fennelly had been one of Snyder’s closest confidants and her and Newman had worked for seventeen as advocates within the shelter community

Many of those who voted to oust Fennelly accused her of monopolizing power, and demanded greater input from more members to “allow the group to move beyond Snyder’s immense shadow and mature as an organization.”[6] However, some housing advocates did not feel the same, and worried that Fennelly’s departure removed a public spokesperson for the homeless at a critical time. “It really is the end of an era. I think homeless people in the city, and to an extent in the country, are losing a champion and simply gaining a housing authority,” said Cliff Newman of Fennelly’s departure. Keith Mitchell, a former resident at the shelter, replaced Fennelly as the new director. [7]

Fennelly’s departure symbolized more than just a change in leadership, but a change in the dominant ideals and tactics of the homeless advocacy movement. Mitchell’s appointment to the director position signified the first time a homeless person directed a shelter in the country.[8] CCNV, which had “long been filled with ‘60s-style idealists” was quickly transforming, filled with more members who were formerly homeless and less bound to the philosophy of CCNV.

Indeed, Mitchell’s approach to managing CCNV differed significantly from Snyder’s, especially in their relationship with the federal government. Snyder had traditionally challenged the federal government in its approach to providing services for the homeless. Mitchell on the other hand, believed that the CCNV had become too isolated, and for the first time in the shelter’s history had planned to accept federal funds.[9] The two leaders also had extremely different views on tactics for advocacy. Mitchell made it very clear that he was not copying Snyder’s activist style; Mitchell chose to focus his efforts on developing a case management plan and emphasized the need for moving people towards transitional housing instead of organizing direct action campaigns and hunger strikes to emphasize the moral right to housing.

This shift at CCNV illustrated a larger change within the homeless and housing advocacy movement, from radical political protest aimed at changing the structures that perpetuate homelessness to that of bureaucratic service through treating the symptoms of the larger problem. In her dissertation, “From Political Protest to Bureaucratic Service: The Transformation of Homeless Advocacy in the Nation’s Capital and the Eclipse of Political Discourse,” Christine Marie Elwell argues that the today’s homeless advocacy movement has become more professionalized and is focused on “managing the homeless problem instead of eliminating it or preventing it.”[10] Additionally, Elwell points out that what it means to be an “advocate” has also changed, shifting from mainly a volunteer base in the 1970s-80s to paid advocates working for non-profits. These broader changes within the homeless and housing advocacy movement, beyond the drastic changes at CCNV, have had broad impacts on the movement as we see it today.

For Mark Anderson, these changes may have been understandable, but they came at a considerable cost.[11]

[1] Anderson, Mark. Interview by Beth Geglia. Digital Recording. Washington, D.C., April 26, 2013.

[2] Rene Sanchez and Christine Spolar. “District to Overhaul Shelter Plan: Emphasis Shifting to Permanent Homes.” The Washington Post. 7 March 1991.

[3] Carlos Sanchez and Ruben Castaneda.“CCNV Members Claim NW Center as Shelter.” The Washington Post. 5 April 1991.

[4] Christine Spolar. “The Void Mitch Snyder Left Behind.” The Washington Post. 8 July 1991.

[5] Brooke A. Masters. “DC to Begin Probe of CCNV Shelter.” The Washington Post. 14 Dec 1993

[6] Brooke A. Masters and Saundra Torry. “Carol Fennelly Ousted from CCNV Leadership Post.” The Washington Post. 14 January 1994.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Rene Sanchez. “A Leader of Homeless Who Walked the Walk.” The Washington Post. 14 February 1994.

[9] Ibid.