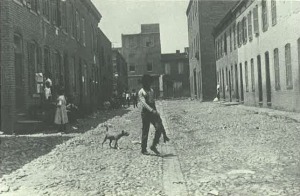

When one thinks of an urban alley, an image of narrow shortcuts filled with dumpsters and fire escapes may come to mind. But alleys have a deeper history in the United States, especially in Washington, DC. Alleys have housed working class communities who lived in small structures off of major residential streets. Many buildings in downtown DC, including the current site of the Community for Creative Non-Violence shelter, stand on land that was once home to these alley communities.

In 1909, Charles Weller observed that the alleys of the nation’s capital, unlike northern ghettoes of concentrated poverty, were dispersed throughout the entire city and mixed in with upper class residences.[1]

Because Washington was a pedestrian city, workers required housing near the center of the city in order to be close to work, so middle class landowners built residences for unskilled workers in vacant rear lots with alley access.[2] In these “integrated” neighborhoods, whites tended to live on the street while the black population resided predominantly in the alleys.

While lack of affordable transportation was a major contributor to the construction of alley dwellings, profit seeking also played a major role in this new distribution of housing.[3] James Borchert observes: “While alley housing was largely a response to the constraints of the pedestrian city, it was also the result of many individual decisions by landowners, builders, and others to an apparently inexhaustable [sic] demand for low-cost housing. The potential for profit, and the efforts to realize it, profoundly affected the nature and character of the alley communities that developed.”[4] Many of the alley houses were crowded, significantly smaller, and built with much cheaper materials than the homes facing the streets. Owners, nonetheless, were able to charge rent due to the housing shortage after the Civil War. As a result, black communities became restricted to alley communities where they developed their own sense of place. People may have lived close together due to the pedestrian nature of the city, but inequality was identifiable in the dichotomy between street and alley dwellings.

In the 1920s, housing advocates attempted to eliminate the slums of Washington’s back alleys as the expansion of the automobile industry made commuting more feasible and placed a greater

demand on space at the center of the city for business.[5] White housing advocates saw business expansion as a better form of land use than alley communities because they believed the alleys were unsanitary and bred immorality.[6]

Reformers “recognized the potential problems associated with displacing the city’s poorest black residents from their alley homes,” but argued that there was no longer a housing shortage so alley dwellers could be relocated.[7] They reasoned that the displacement of black residents from downtown would improve “the character of the people” who moved outwards and open up downtown property for federal government workers to move in.[8] They soon gained the support of Congress, and new legislation created the Alley Dwelling Authority in 1934 and gave it broad power to condemn these alley homes.[9] The rapid expansion of the government during the New Deal and World War II, however, pushed housing prices upward and led to a significant housing squeeze. The movement to eliminate alley dwellings, though celebrated by the DC Alley Dwelling Authority, sacrificed affordable housing for the sake of business and government expansion downtown.

Unfortunately, the argument that affordable housing was widely available proved false as the growth of the government under the New Deal contributed to the housing crunch in the city, and Washington’s pursuit of “urban revitalization” elevated racial conflict in the city. As white housing reformers were pushing for development and revitalization in the downtown area, black alley dwellers were struggling to fight dispossession.

[1] James Borchert, Alley Life in Washington: Family, Community, Religion, and Folklife in the City, 1850-1970 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1980), 1.

[2] Borchert, 26.

[3] Borchert, 15.

[4] Borchert, 23.

[5] Howard Gillette, Jr., Between Justice and Beauty: Race, Planning, and the Failure of Urban Policy in Washington, D.C. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 136.

[6] Gillette, 136.

[7] Gillette, Jr., 137.

[8] Gillette, Jr. 140.

[9] Gillette, Jr. 139.