Mitch Snyder was the most recognizable activist for homelessness in Washington, DC, earning the honorary renaming of 2nd Street NW in front of the Community for Creative Non-Violence shelter to Mitch Snyder Place. Yet his activism began while he served time in prison before he moved to DC.

Snyder’s background resembled that of many caught up in the prison system. Born in 1943 in Brooklyn, New York, his parents divorced when Snyder was nine. His father financially neglected his children and left Snyder responsible for supporting the family. As a teenager he was arrested several times for breaking into parking meters. As a result, he was sent to reform school in upstate New York. He dropped out of high school and worked various jobs as a vacuum cleaner and washing machine salesman, as a job counselor, and as a construction worker. He married Ellen Kleiman in 1963 and had two sons. Separated from his family, in 1970 he was arrested for auto theft in Las Vegas. Convicted, he was transferred to federal prison in Danbury, Connecticut.[1]

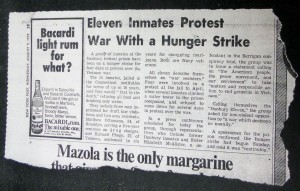

While in prison serving a three-year sentence from 1970 to 1972,[2] Snyder occupied himself with the penal system’s institutionalized injustices and developed his strategy of protest by fasting. He and ten other inmates, known as the Danbury 11, fasted in protest of both the Vietnam War and unjust prison discipline.[3] Claiming the need for better medical facilities to care for the fasting inmates, the penal system transferred the protestors to Springfield, Missouri.[4] Director of Prisons Norman Carlson transferred everyone except Snyder back to Danbury once their health stabilized, so Snyder fasted again until they returned him to the prison closer to his family.[5]

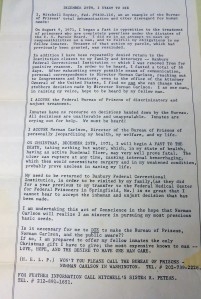

In addition to fasting, Snyder wrote endless letters to politicians and submitted articles to newspapers and magazines.[6] He understood that power came from making his voice heard and getting his story out to a wider audience. When asked to describe himself, Snyder wrote, “he has come to understand that resistance must be a lifestyle, not simply a tactic. He continues to learn, he continues to act.”[7] Fighting inequality in the federal government’s treatment of people—whether they were the Vietnamese, the incarcerated, or the homeless—stimulated Snyder’s intellectual prowess.

Snyder was not the only person organizing action for social justice. Through his activism in prison he made important connections that would shape his life after prison. While serving time in Danbury, Snyder befriended and organized with Daniel and Philip Berrigan, two anti-war priests who had been imprisoned for destroying draft records. The brothers strongly influenced Snyder, who became a follower of their radical brand of Catholicism. After their release, Snyder and the Berrigans teamed up in New York for anti-war marches protesting the US’s involvement in Vietnam. Immediately following those marches, another former inmate imprisoned with Snyder at Danbury, Tom Ireland, asked him to join CCNV in 1973, igniting Snyder’s influential work with and for the homeless.[9]

[1] Ellen Snyder. “Questionnaire About Mitch Snyder” (1970). Snyder Box 03 Folder 11. Special Collections Research Center, The George Washington University Libraries; New York Times, July 6, 1990.

[2] 1972_SnyderSentenceComputationRecord.jpg. Snyder Box 03 Folder 15. Special Collections Research Center, The George Washington University Libraries.

[3] “Another Fast Staged Here.” (1971, Oct 19). Snyder Box 03 Folder 25. Special Collections Research Center, The George Washington University Libraries.

[4] Snyder Prison Locations and Dates notecards. Snyder Box 01 Folder 09. Special Collections Research Center, The George Washington University Libraries.

[5] *Need Citation

[6] Mitch Snyder. “The Crime of Silence.” The Village Voice (1972, May 11). Snyder Box 03 Folder 25. Special Collections Research Center, The George Washington University Libraries; Mitch Snyder. “Letter to Congressman Anderson.” Personal correspondence (1971, Dec 14). Snyder Box 02 Folder 07. Special Collections Research Center, The George Washington University Libraries.

[7] Mitch Snyder. “Anatomy of a Prison Strike” (nd). Snyder Box 05 Folder 01. Special Collections Research Center, The George Washington University Libraries.

[8] Mitch Snyder. “Anatomy of a Prison Strike” (nd). Snyder Box 05 Folder 01. Special Collections Research Center, The George Washington University Libraries.

[9] Christine M. Elwell. “From Political Protest to Bureaucratic Service: The Transformation of Homeless Advocacy in the Nation’s Capital and the Eclipse of Political Discourse.” PhD Dissertation (Washington, D.C.: American University, 2008) 55; New York Times, July 6, 1990.